I’ve been working a lot with APIs during the last few years, either developing them or integrating with third party APIs. So I’ve decided to gather some of the knowledge I gained along the way and write about it here. Many of the APIs I’ve integrated with didn’t follow any kind of pattern, so their documentation had to be consulted more often than if they were following some of the points below. Because of that, some of them couldn’t even be considered RESTful APIs.

What is REST?

REST means Representational State Transfer, and it is a software architectural style that defines a set of rules to be used when creating APIs. The APIs that conform to the REST style are called RESTful APIs. First, you need to create one or more endpoints and expose them to your clients. Then, your clients are able to access them via HTTP using the correct HTTP methods.

HTTP methods

The GET method happens when you open a website and it retrieves an image from the server, for example. The POST method is often used on forms in websites, so your data is not sent in the URL (query string), but in the body of the request in this case. A RESTful API will use these two HTTP methods in their specific cases, but also some others like PUT and DELETE.

Let’s see some points to take into consideration when designing an API.

Endpoints should be nouns, not verbs

Think of a resource you have in the system. For example, you have a collection of employees. If your client wants to retrieve a list of employees, he doesn’t need to remember he has to access the URL /getEmployees. Or even worse, what if this method was called /getAllEmployees, or something else? Then your client would have to remember if the method for deleting an employee was /removeEmployee or /deleteEmployee, for example, and use the HTTP Method POST for that?

What if you could follow a pattern that would make much more sense for everybody? The HTTP protocol already comes with methods you can implement on your API for your client to interact with, so that makes it more intuitive.

Let’s suppose you have a collection of employees in your database, and you want to return all of these employees.

Then your client will make an HTTP GET request to the /employees endpoint for that.

The most used form when naming an endpoint is the plural, so employees instead of employee in this example, as we’re returning a list with all the employees.

It makes much more sense this way, but if you insist in using the singular form (I wouldn’t recommend), it’s important that you keep the same pattern also in the other endpoints you create.

Use the correct HTTP methods

Following our GET /employees example, which returns a list of employees, what happens if we need to create, update, delete an employee, or retrieve just a single employee? There are HTTP methods for each of these cases:

POST

The HTTP POST method is the one for when you want to create a resource, so the client will POST to /employees, sending the data in the request body instead of in the query string. If the request body contains any array, the best practice is to stringify that array. I’ve seen people sending something like this for the server to parse:

1

2

3

4

5

6

{

"termsOptions[0].key": "optionSMS",

"termsOptions[0].value": "true",

"termsOptions[1].key": "optionPhone",

"termsOptions[1].value": "true"

}

instead of just simply sending a stringified array. This would be better sent like that:

1

{ "termsOptions": [{"optionSMS": "true"}, {"optionPhone": "true"}] }

or even better, use an object instead:

1

{ "termsOptions": {"optionSMS": "true", "optionPhone": "true"} }

PUT

The HTTP PUT method is the one you use when you want to update a resource. Before accessing this endpoint, the client will need to retrieve the employees, so it is able to know the id of the employee it wants to update.

An endpoint with a PUT request is accessed by sending HTTP PUT to /employees/:id, being :id the id of the chosen employee. In the body of the request must be the object that represents the employee, with the changes the client needs to make.

Ps: I’ve seen some (very few) APIs implementing the HTTP PATCH method to allow the partial update of a resource, so from experience, that’s not much used. If you need to update your resource only partially, though, then use PATCH instead.

DELETE

The HTTP DELETE method is used when you want to delete a resource. Same way as with the PUT request, the client will need to have retrieved the employees before, so it is able to know the id of the employee it wants to delete.

An endpoint with a DELETE request is accessed by sending HTTP DELETE to /employees/:id, being :id the id of the chosen employee. In this request, nothing goes in the body.

GET

Following this same pattern then, what if we want to get a single employee? That’s right, we can call it the same way we did when using the PUT request, but changing the HTTP method from PUT to GET. So it would be GET /employees/:id, being :id the id of the chosen employee.

Safe or idempotent

A GET request is safe and idempotent. An HTTP method is considered safe when invoking that method doesn’t change the state of the resource. It doesn’t matter how many times you run GET /employees/1, for example, that will not change anything in that employee (it won’t be updated or deleted). When you get the same response no matter how many times you call the same endpoint, this means it is idempotent.

A POST request, for example, is not safe nor idempotent, as it always creates something and the response is not the same every time you call it.

PUT and DELETE requests are not safe but are idempotent.

When any of these methods are consumed in your API, a response should be returned to the client, right? Let’s see more about the response then in the next topic.

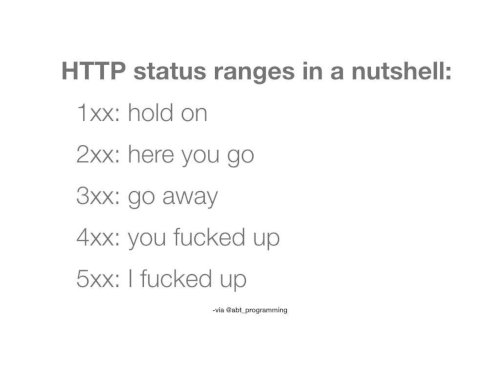

Use the correct HTTP codes

The HTTP protocol has a series of codes that can be used for specific cases. Many people know already (even some who don’t work directly with IT), that 404 means NOT FOUND, so that’s a valid HTTP code that should be returned by our API when a resource is not found.

The code 200 means OK and should be returned when the request happened successfully. It is mostly used for GET requests.

When you have an endpoint that creates a resource, it should return the status 201, which means CREATED. Makes sense, right?

If when trying to create a resource, the client sent malformed data to the endpoint, it should return 400, which means BAD REQUEST.

401 is for when the client is unauthorized, 500 for when there’s an internal error in the server, and so on.

Unfortunately, I’ve seen many APIs always returning 200 OK for everything. Please be nice and don’t do that, as there are codes widely used to explain each case.

I’ve also seen some returning always 200 as the status code, but some different status code in the body of the response. That is redundant, as there’s already a place for the status code in the response, outside the body. That would be less worse than returning always 200 as the status code but no other status anywhere at all, though.

Another thing I have seen but wouldn’t recommend would be to create some random status code, like 398 or 521, for example and return it in the body. There are several status codes that exist and can be used already, so there’s no need to invent new ones. Let’s follow the correct HTTP status codes?

If you wanna know more about other HTTP status codes, here are some links:

-

If you like cats

-

If you prefer dogs

-

If you are a very serious person / would like a deeper explanation

Document your endpoints

If you are building an API, then it means you’ll be integrating one or more clients (frontend, mobile, desktop) with it soon. It is important to write a good documentation on how to use the endpoints you’re exposing with your API, so other developers that will implement these clients, or even you in the future, are able to know how to proceed.

If you document well your API endpoints and how to work with them (and keep the documentation updated), developers will ask you less questions and your company will save time/money.

I’ve written a post about APIDoc for that purpose, but lately I’ve been using Swagger instead (I’ll write a post about it soon).

Version your API

Software is like a living organism, constantly changing and evolving. Your business and processes will change over time, requirements will change. If you work with Software Development, you need to learn to embrace change, so do yourself a favor and start versioning your API from the start.

The best way to version an API is to include the version in the URL. For example, if your API base for the employees endpoint is /api/employees, change it to /api/v1/employees

If the new requirements will introduce a breaking change, then you can create an endpoint under v2, as /api/v2/employees and keep it running side by side with the /api/v1/employees endpoint, so the clients that are using the v1 are not broken with the update.

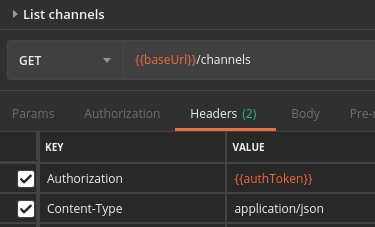

Send the authorization token in the header instead of in the URL

There’s something called “Authorization” header which you can use to send your token, then there’s no reason to expect that to be sent in the query string, even less in the request body.

Use pagination

Imagine you have thousands of employees in your collection, and the client consumes the GET /employees endpoint. If you have no pagination, then the response can take a really long time or even make the service unavailable if there are thousands of requests for the same endpoint without pagination.

So always return paged results when there’s a list in your response. The API can accept parameters in the query string, such as page and limit, to inform which page and how many rows to be returned, for example.

Check response size and never include images

Watch out for the size of your responses. Imagine a response of some hundreds of Kb multiplied by thousands, when your API is live (think about the future). It’s better to keep it as slim as possible and not include unecessary data in it.

Also, please use an object storage service like AWS S3 for images, for example, and return only the link for those images instead of the code of the image as base64. Yes, I’ve seen that happening as well and the response gets huge!

You can easily check the size of the response on Postman.

Use SSL, but don’t configure that directly in your API

SSL is very imporant in order for your API to be more secure. Your API doesn’t need to implement it, though. It’s better to leave this to your load balancer, reverse proxy or API Gateway, so your API can be started in cluster mode behind it and not be exposed to the outside world, receiving data via local network or unix sockets.

Always validate input

When web development used to be all in one layer, with the frontend code built by the server and the HTML outputted as static content, it seems that there used to be more focus on input validation. Now that we have frontend and backend separated in two layers, many times we see the validation happening only in the frontend. That can obviously lead to security risks, so it’s very important to always validate user input in your API as well.

Do not rely on the clients to implement validation, but implement it in the API as well, returning the correct HTTP status codes according to the case.

Test your API with automated tests

Improve the quality of your code and be sure your API is responding with the correct HTTP status codes for each case, by writing automated tests. When you have tests, it’s easier to add new features because you know better if your changes are breaking what is already working, for example. This can take longer in the beginning to implement, but will save you time in the future.

KISS (Keep it simple, stupid)

I love this software principle, because it avoids me doing unecessary stuff and makes the code easier to understand and evolve in the future.

For example:

-

Always return the same format of data. Stay consistent. Don’t have many different kinds of error objects, but stick to only one, so your clients know what to expect.

-

Do not include unecessary data in the response. Don’t expose more than you think needs exposing. If something is not needed for any client, then there’s no need to expose it.

Conclusion

Building an API sometimes can be a complicated task, but if we follow best practices and if we are consistent and keep it simple, a lot of time can be saved and future headache avoided.

What are some of the best practices you’ve been using? If you have any tips or know of something I forgot to mention, leave a comment below :)